[This post is part of a series on Coaching Highlights from coaching Columbia Business School students. If you don’t see a Table of Contents to the left, click here to view the series, where you’ll get more value than reading just this post.]

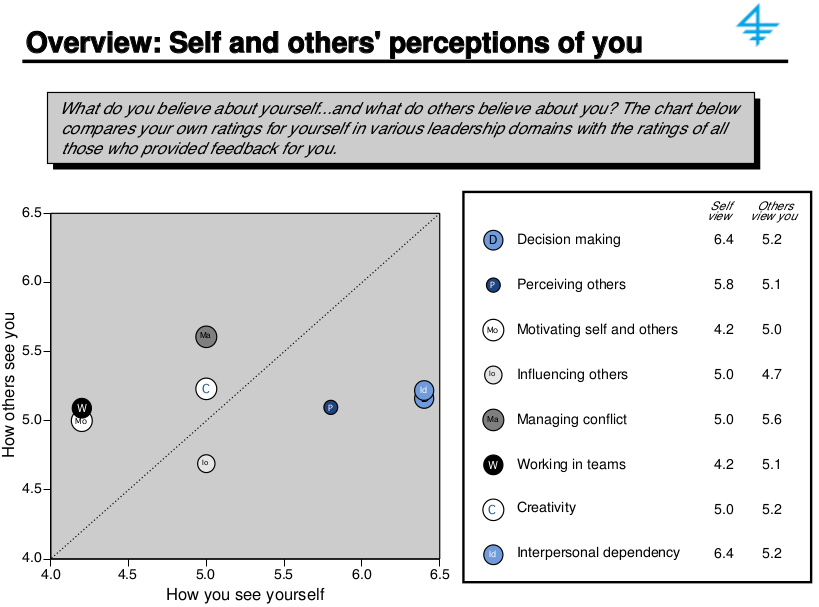

Just the structure of yesterday’s charts teaches a lot about leadership. They emerged as main tools for communicating leadership ability and guiding improvement so even if you’re never the subject of one, you can still benefit from knowing about them. Let’s see a few reasons why. Let’s look at one again.

The chart breaks leadership into sub-skills

The chart breaks leadership into sub-skills

My Core Leadership class at Columbia began with asking the professor asking us to define leadership. It’s notoriously difficult to define. So instead of trying to, he pointed out that it has a behavior component and that if you behave in certain leader-like ways, people would treat you like a leader. Once they do, you feel more like one, creating a cycle that, if you keep at it, leads to your becoming a leader. (I like this perspective. I don’t need to know exactly what something is to know that if I do as well as I can and am improving as fast as I can, I can’t to better, which is my perspective on the questions “What’s the meaning of life?”.) Those behaviors are skills and you can learn to practice them, even if you don’t know what leadership means. Just saying “act like a leader” won’t help someone act like a leader. But breaking them down into areas with more specific skills does help. Columbia breaks its skills down as I described yesterday and as illustrated above

- Decision making

- Perceiving others

- Motivating self and others

- Influencing others

- Managing conflict

- Working in teams

- Creativity

- Interpersonal dependency

You can break down leadership in other ways — with more, fewer, or different categories — but this division works well. As an exercise, you might ask yourself if this list is complete, if it has unnecessary elements, and how someone may have come up with this breakdown. I find it interesting and informative to analyze leadership in more detail. To review, breaking down leadership performance into sub-skills for both evaluation and learning teaches a few things about leadership

- Leadership is based in behavior

- Leadership contains several sub-areas (listed above)

- You can learn its sub-skills more easily than trying “to be a better leader”

The chart rates you subjectively

In many fields people try to rate performance on objective measures — how quickly you can do relevant tasks, how consistently you perform, how much you increased sales, etc. Leadership may have some objective measures, but ultimately you’re leading other people. How they respond to your behavior is how you lead. The result is that how other people see you subjectively determines how well you lead. You can’t measure leadership skill with a ruler or stopwatch. If you want to know how well you lead, you have to find out how others see you. One of the best ways is to ask, which this type of review does, with the added benefit in most cases of anonymity. By asking people to look at you in sub-skills you get a more detailed picture.

The chart compares your perception against others’

How well you lead still doesn’t determine how great a leader you can become. People don’t wait around in a vacuum waiting for you to show up to lead. They don’t decide to promote you to leadership positions based on your skills alone. Other people want to lead too. Even if they don’t want to, others emerge as leaders, sometimes unwillingly. If you want to lead, you have lead better than the alternatives, so you benefit from seeing how you compare. Another way of looking at this comparison is that you need to calibrate your leadership skills against something. Since we saw no objective measure exists, other people’s leadership skills emerge as a great comparison. Another great comparison not shown in this report is against you in the past. That requires multiple tests over time, which, unfortunately, a few-month course in school couldn’t do, though you might find happen in your career.

There is always some spread in the dots

People get rated differently in some areas than others. This chart shows that you may score higher or lower in an area than another and that you may score higher or lower as rated by yourself or others. The spread reveals your strengths and weaknesses as perceived by yourself and others. Knowing these strengths and weaknesses helps in two main ways

- Knowing your strengths tells you where you can help most

- Knowing your weaknesses tells you where you need the most help and where to hold back from contributing if others can do better

- Knowing your strengths and weaknesses helps you decide where to improve.

Speaking of knowing where to improve, most people, when deciding what leadership area to work on most or first, work on their most extreme weakness — the dot furthest down and left. I have no problem with that strategy, but point out working on any other dot can help as much.

- Working on the highest right-most dot can make you a specialist, which can add value to many teams.

- Working on a dot the farthest from the diagonal can align your self-perception most with your peers’.

- Working on a dot where you feel most motivated — maybe you want to work on decision-making these days or you just found a great book on motivation — may yield the fastest or greatest results.

- Working on a dot related to a current need in your life — maybe you’re in the midst of a lot of conflict and need the most help in that area or your team’s decision-maker just left — may improve your life or team the most.

- Moving any dot by the same amount up or to the right improves your leadership ability, so choosing any dot will help, as long as you work on it.

- Other strategies can work too.

Which leadership development strategy works best for you depends on your greater life or professional strategies.

There’s a diagonal line on the chart

The diagonal line for which dots on it show you perceive yourself how others do, which I think of as a line of high self-awareness. Since no one is perfect in all areas, everyone has areas of relative weakness. To me, weakness could come in two main ways. First, you could have low numbers but close to each other — that is, close to the line — meaning you and others both view you as performing poorly. To cure this problem in the moment, you and your peers both know to try to get someone else before you because you don’t do well there. In the long run, of course, you can try to improve this weakness or bring someone else permanently on the team with skills to complement yours. Second, you could also have disparate numbers, meaning dots far from the diagonal. Not everyone recognizes this problem, and you might never notice it without a test like this. Points below the line imply you see yourself as better than others. You may act like a bull in a china shop, doing things others don’t think you do well. Points above the line indicate missed opportunity. People think you can do things, but you don’t, so you don’t do them. Improving in areas below the line can be easier than ones above the line, since you only have to learn things you didn’t know before. Improving areas above the line often requires become aware of things you didn’t know about yet others did, which can be harder, since you’ve been missing them all this time. Let’s also look at the second chart.

This chart compares how others see you versus your peers

This chart compares how others see you versus your peers

Most of the properties from the previous chart apply to this one. One big difference is that this one compares your abilities to your peers’. This alternative comparison helps you improve your leadership skills in two ways. First, you don’t get promoted in a vacuum, you get promoted compared to others. Likewise, people don’t follow you in a vacuum, they follow you if no one else leads them better for them. Knowing how you compare to them helps you understand where to work. Secondly, without anything to compare yourself with, you don’t know how well or poorly you do. Comparing with others calibrates your skills with peers’. Whew, long post! More tomorrow. I hope this helps you become a better leader.

Pingback: A sample 360-degree feedback report: more detail » Joshua Spodek

Pingback: Coaching highlights from coaching Columbia Business School students: Weaknesses are often strengths misapplied | Joshua Spodek