Months ago I bought a battery (used off Craigslist) to power my apartment. They call them power stations, partly to sound more impressive, partly since they can receive and deliver electric power in many ways.

The process started years ago, when I started reducing my electric power demand to where a battery would suffice, and I dropped my demand to a couple dollars worth per month.

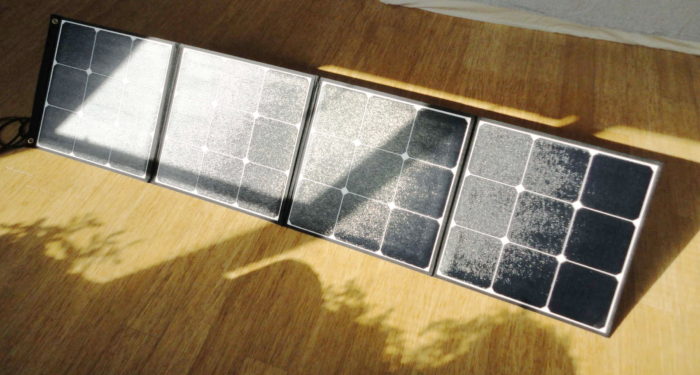

The other day I bought the solar panels (also used off Craigslist). Portable ones like I bought cost more than the bulky ones most people put on their homes, but I anticipated carrying mine up and down eleven flights each way to my buildings’ roof for more sunlight.

Simple set-up

I figured I’d need to read a lot in the manuals to figure out how to make them work. On the contrary, I just connected the wires from the panels to the matching wires in the power station. It beeped. The display came on and showed it was powering. I couldn’t believe how easy it was.

It’s a clear day in February in New York City, so the sun doesn’t go high up in the sky but no clouds blocked the sunlight. My windows need cleaning, so they cut some light. Here’s the set-up:

The battery is on the right, the panels on the left. You can see from the diagonal of the shadow that the sun is low on the horizon. Still, I’m getting power not from the grid. I was going to take the picture earlier, but my camera’s battery needed charging. If you look on the battery’s right, you can see the charger for the phone battery. I charged the phone with solar power.

So simple, I should have started earlier

My physics degree and engineering experience held me back. I expected to need to apply what I knew about energy and power, like the difference between Watts and kilowatt-hours.

I didn’t. It turns out these technologies are mature enough, I didn’t need any physics to start. The details of the units don’t matter. You only need to know one number tells you how much juice the battery holds, the other says how fast it can supply it. The details don’t matter. I worked out what the numbers mead with experience. I’ll clarify in describing the set-up.

The set-up

Here are a couple shots of the battery and its display:

The ’35’ on the left in the display is saying that with the amount of light charging it now, it would take 35 hours to charge it. The ’30’ in the circle means it’s 30 percent charged. You can see the camera battery charger connected on the left.

It read 15 hours to charge to full when I plugged it in, around noon, which implies a few cloudless days to charge it to full, which I would need to power the pressure cooker to cook a full load of famous no-packaging vegan stew.

But I can improve that performance a lot. I believe I can, anyway, and bought these things to experiment. This set-up was just on my floor.

You can barely see it in the picture below, but the panels have two eyelets on the left. I expect I can run some rope through them and let the panels hang outside my windows for direct sunlight. I can also bring them to the roof for direct sunlight and the exercise of climbing the stairs with heavy panels and a battery.

My electric bills start on the 7th of the month, so I have a couple weeks to experiment and see if I should try turning off the circuit to my apartment on March 7, still be an earlier step than contacting the power company to turn it off for a month.

Reduce, Reduce, Reduce

If this experiment works, I will see it less a proof that solar power can work so much as evidence of how much less power we need for health, happiness, productivity, fun, and more.

The result will be freedom as much or more than anything else. We’ll see. It could happen that I try to make stew, drain the power to zero, and end up unable to connect to the internet. Even if so, that result would only show me how to prepare for those cases too.

Limits

Between buying the battery and the panels, I started discovering how much solar relies on fossil fuels and other nonrenewable resources. Until I learn otherwise, I consider solar power not renewable (except when powering plants to grow). It’s more like methadone compared to heroin: still a serious problem, but if your goal is to stop, it can help.

So I’m advancing weaning myself off my addiction to polluting behavior. I have a long way to go and can’t see past some limits. My building’s hall lights run on power I can’t turn off. I take hot showers, though relatively short at about a minute or two each. I use the laundry machines in the basement (I tried a hand washer, but it broke). I use the elevator a couple times a year.

My main goal in consuming less without sacrificing quality of life, actually learning to increase it, is only partly personal. Roger Bannister’s breaking the four-minute mile opened the gates for many others too. He was a doctor too, and could have just said “As a medical doctor, I can tell you that running a mile in under four minutes is possible,” but no one would have cared. Doing it spoke louder than words.

I hope to be a Roger Bannister for many, maybe you.

Pingback: My first solar-powered famous no-packaging vegan stew » Joshua Spodek